Life Transitions & Grief

Birth is our first experience of transition.

Our entry into the external world may be fast or slow, smooth or painful, natural or aided by forceps or caesarian delivery. Whatever the circumstances in which we drew our first breath, we experience a ‘dramatic change from one state or situation to another’ – a transition. Some of us enter the world already in motion and protesting loudly, others seem tranquil or bemused, and a minority struggle to survive outside a protective cocoon.

If researchers followed our progress through life from first breaths to last, I wonder if those initial responses to transition would remain a characteristic of our personalities and our physical being? I found myself laughing as I thought about this and remembered being told that I was facing the wrong way when my mother was in labour and had to be turned by the obstetrician. I’ve been directionally dyslexic ever since.

Throughout life, every developmental ‘stage’ is a transition. Our physical, emotional, cognitive and language abilities change rapidly in the first two years as a relatively linear progression in ideal circumstances but are inevitably affected by health, family and social circumstances and events. For example, the birth of siblings can change our position in the family order from being an only child to eldest child, or from second to middle child and so on, a transition that usually involves an initial, if not lifelong, adjustment. Some children handle the transition smoothly, while others launch themselves, or are launched, into sibling rivalry that characterizes their contribution to the family dynamic forever.

Throughout life, every developmental ‘stage’ is a transition. Our physical, emotional, cognitive and language abilities change rapidly in the first two years as a relatively linear progression in ideal circumstances but are inevitably affected by health, family and social circumstances and events. For example, the birth of siblings can change our position in the family order from being an only child to eldest child, or from second to middle child and so on, a transition that usually involves an initial, if not lifelong, adjustment. Some children handle the transition smoothly, while others launch themselves, or are launched, into sibling rivalry that characterizes their contribution to the family dynamic forever.

The list of transitions life confronts us with is seemingly endless. For example, starting pre-school, big school, primary school, high school, and for some, tertiary education. Teenage friendships and our responses to their emotional ups and downs help to prepare us for transition into adult relationships with their attending responsibilities. Leaving school and joining the workforce is another transition, often co-existing with our entry into the world of dating, falling in and out of love, perhaps eventually finding a life partner.

Becoming parents and creating a family is a huge transition for most of us, requiring us to relinquish our youthful narcissistic expectations of life and replace them with an ability to be other centered. Every step involved in raising children can involve transitions, often accompanied by mixed emotions. When they finally leave home, the mythical and sometimes longed-for end of our full-time responsibility for their wellbeing, we may experience grief.

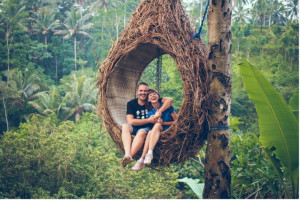

The Empty Nest

When my own children left home, I remember feeling proud of their ability to earn a living and to make decisions about the way they wanted to live their lives. But, living alongside those feelings, I also felt the kind of sadness described as ‘the empty nest syndrome’, usually, and perhaps inaccurately, attributed solely to women. I remember walking from room-to-room, sad about the ending of that part of my role, knowing that the images associated with each room would now be relegated to the memory box of dreams.

When my own children left home, I remember feeling proud of their ability to earn a living and to make decisions about the way they wanted to live their lives. But, living alongside those feelings, I also felt the kind of sadness described as ‘the empty nest syndrome’, usually, and perhaps inaccurately, attributed solely to women. I remember walking from room-to-room, sad about the ending of that part of my role, knowing that the images associated with each room would now be relegated to the memory box of dreams.

A New Nest

In my own life, the nest didn’t remain empty for long. It was eventually filled with the comings and goings of children and their partners, grandchildren, and eventually great grandchildren, each addition representing a transition in terms of roles, feelings and responses. Most of these changes have been relatively straight-forward transitions but have been interspersed with those that have proved more complex. For example, separations, divorces and bereavement.

In my own life, the nest didn’t remain empty for long. It was eventually filled with the comings and goings of children and their partners, grandchildren, and eventually great grandchildren, each addition representing a transition in terms of roles, feelings and responses. Most of these changes have been relatively straight-forward transitions but have been interspersed with those that have proved more complex. For example, separations, divorces and bereavement.

My husband and I have also experienced the transition from full time work into semi-retirement, a gradual and privileged process for us which has allowed us time to process the losses and gains involved. Other folk may be catapulted into that world suddenly, without choice, as a result of injury, ill health or retrenchment. Grief in those circumstances is often painful, misunderstood, and sadly, often unsupported.

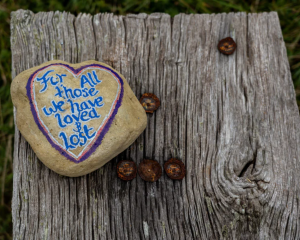

The Transition of Bereavement

The transition created by bereavement is very rarely one of choice. If someone we love has suffered over a prolonged period and our helplessness to alleviate pain has rendered us resourceless and exhausted, death may initially be experienced as relief. But, as energy returns, we inevitably face the difficult transition into the long haul of learning how to live with grief, how to love in absence and live with pain and feelings of emptiness.

The transition created by bereavement is very rarely one of choice. If someone we love has suffered over a prolonged period and our helplessness to alleviate pain has rendered us resourceless and exhausted, death may initially be experienced as relief. But, as energy returns, we inevitably face the difficult transition into the long haul of learning how to live with grief, how to love in absence and live with pain and feelings of emptiness.

Sudden death catapults us into that same world without warning, without time for rehearsal of our changed role, without opportunity to attend to unfinished business, without the possibility of expressing important thoughts and feelings or of giving one last hug. Whether death is slow and anticipated, or sudden and without warning, the process of transition into the world of living and loving in absence is frequently long, slow and painful.

Most transition experiences throughout our lives can be managed effectively if we have opportunities to share our experiences with others who understand. Grief after bereavement is one transition that almost inevitably necessitates that kind of help. When we are bereaved, we need a safe environment that enables us to express grief in our own way, activities that provide respite through distraction, opportunities to honour and remember the person who died, and a way of making our lives continue to have meaning and purpose.

Role Transitions in Bereavement

The death of someone we love may change our role from husband or wife to widow or widower, from parents of living children to parents of dead children, from parents of two or more children to parents of one or two living children. We grieve the loss of role as well as the person who died.

The death of someone we love may change our role from husband or wife to widow or widower, from parents of living children to parents of dead children, from parents of two or more children to parents of one or two living children. We grieve the loss of role as well as the person who died.

When a parent dies, children may not only grieve the parent who died but also fear the death of their surviving parent. They may also fear the inability of the family unit to survive and may consciously or unconsciously try to fill the empty role.

When a sibling dies, children may face the difficult role transition of becoming an only child, or the oldest instead of middle child, their grief complicated when they feel as if they have lost their parents to grief. Their acting out behaviour is often an attempt to call their parents back into life, a way of saying “I’m still here, I need you.”

Whatever the circumstances, role transition can be complex and distressing and necessitate compassionate understanding and support.

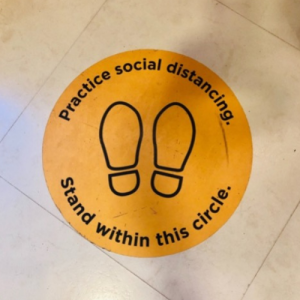

Current Transitions – Living in a Pandemic World

No matter what our age, ability, social standing, financial status or cultural background, the advent of Covid-19 into our lives has made an indelible impact. Everything has changed – from the way we experience birth, death and all significant milestones and events in between, to the way we dream, plan and live our everyday lives.

No matter what our age, ability, social standing, financial status or cultural background, the advent of Covid-19 into our lives has made an indelible impact. Everything has changed – from the way we experience birth, death and all significant milestones and events in between, to the way we dream, plan and live our everyday lives.

Initially, we were catapulted into the ‘lock down’ world of isolation, forced to leave our previous ‘free range’ world, to draw on our financial, intellectual, creative, adaptive, and compassionate resources to live and work in close proximity to some while distant from others. There were positive as well as negative aspects to this new experience and we probably learned a lot about our personal strengths and weaknesses, and our ability to cope in difficult circumstances.

Life has been hardest of course for those with serious health problems, for those who have been hospitalized, for older people in nursing homes, for people dying or bereaved, and for women giving birth. Weddings have been postponed, travel plans shelved, celebrations cancelled or diluted, and hope has been challenged.

Somehow we managed to survive while we believed the disruption to our familiar way of living was to be short lived, harder to adapt now that we know we’re in this new world for the long haul.

How do we keep hope alive? Adjust our goals? Sustain our new ways of remaining connected? How can we plan and experience holidays that give us time out and a change of scenery? How do we find creative ways of celebrating without paying the price of spreading infection? How can we support people living alone, living in nursing homes, or sick in hospital? How do we join forces to mourn those who die? How can we grieve and support others who are grieving? How do we come to terms with change that is permanent and keep children and young people from falling into pits of despair?

As we have always done – we need to make sure that our own symbolic oxygen masks are securely attached before we try to help anyone else. We need to brainstorm ideas with friends, relatives and colleagues who can think outside the square. Discussion groups, perhaps smaller in size than in the past, and enjoyed in the open air when weather permits, could be productive. Or we may have virtual discussion groups via the internet that can take the place of get togethers in crowded coffee shops or enclosed work areas.

As we have always done – we need to make sure that our own symbolic oxygen masks are securely attached before we try to help anyone else. We need to brainstorm ideas with friends, relatives and colleagues who can think outside the square. Discussion groups, perhaps smaller in size than in the past, and enjoyed in the open air when weather permits, could be productive. Or we may have virtual discussion groups via the internet that can take the place of get togethers in crowded coffee shops or enclosed work areas.

We can plan holidays in our own country or take frequent breaks close to our own homes. As I write, my mind travels back to memories of my early life, ‘the olden days’ as my great grandchildren like to call them, before TV or the internet, and the fun I enjoyed just being outside, riding my bike, surfing, sitting round a campfire, visiting family farms, train trips, and simple holidays. Not so strange then that those are the experiences I have begun mentally re-creating and plan to continue into the foreseeable future. Things to look forward to.

On a day-to-day basis, my husband and I will continue the routine we began two years ago, of sitting together every evening close to sunset, outside when possible, enjoying a glass of wine and remembering – the people we love, both living and dead, the places we’ve visited, the experiences we’ve shared and our hopes for the future. We’ll enjoy the changing seasons, remain connected to people important to us, and continue to contribute to life for as long as body and mind allow. I hope you’ll join us symbolically at ‘happy hour’.

On a day-to-day basis, my husband and I will continue the routine we began two years ago, of sitting together every evening close to sunset, outside when possible, enjoying a glass of wine and remembering – the people we love, both living and dead, the places we’ve visited, the experiences we’ve shared and our hopes for the future. We’ll enjoy the changing seasons, remain connected to people important to us, and continue to contribute to life for as long as body and mind allow. I hope you’ll join us symbolically at ‘happy hour’.

If you have any creative ideas we could use to help sustain hope, excitement and the joy of life in people of all ages whose hearts ache from grief, I’d love to hear them. You can write to me on: [email protected], share them with the team at the NCCG or we welcome your comments below.

Help

Help is always available at the National Centre for Childhood Grief or by contacting our outreach service.

Dianne McKissock OAM

NCCG Outreach Support Service

Email support for dying and bereaved people and anyone involved in their care

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!