Love, Loss and Grief in a Time of Enforced Isolation

What a beginning we have all experienced to the year 2020 – a year that held so much promise, so much to look forward to. The numerical aspect – 2020 – had an almost magical sound, somehow like 2020 vision that might give everyone a fresh start – but the magic aspect has long passed.

As a nation, we didn’t have time to process, let alone recover, from the physical, emotional and financial effects of devastating summer bushfires and distressing floods before we were hit by a pandemic. A once in one hundred year event, history in the making – something few of us really believed we would experience in our lifetime.

For many, it’s still hard to believe – this fight with an unseen enemy – particularly for very young people, and those hardy souls with robust health and energy who believe they are invincible. Others, whose regression button is easily pressed by anything that remotely smacks of an order, of being told what to do, seem to choose to doubt the seriousness of the threat that COVID-19 poses, even if they acknowledge its existence.

On the other hand, those who are physically or psychologically vulnerable may be almost overwhelmed by the fear of contagion, and yet another group super vigilant because of their concern for the wellbeing of others. For these latter two groups, it makes sense to obey the rules of social distancing and self-isolation, but, no matter where we fit on the acceptance and compliance graph, most of us are already missing physical contact with family and friends. And we’ve only just begun.

Initial Thoughts

How do we pace ourselves when we don’t know how long ‘the long haul’ will be? Through trial and error. We’ll all have to find our own ways of creating enough quality moments to sustain our emotional and physical wellbeing for however long the ‘haul’ turns out to be. At the moment, it’s a bit like trying to guess the length of a piece of string which you haven’t seen.

Every organisation under the sun seems to be sending out suggestions or prescriptions for how to structure time, sustain energy, or constructively use any pockets of energy that might be threatening to explode. I don’t want to do the same, but I probably will, even though I’ll do my best to make this more like a conversation. Well, a monologue really.

I’ll begin by talking about me, and invite anyone reading this to tell me about you. My contact details are at the bottom of this Blog.

About Me – Experiences of imposed Isolation and Isolation by choice

Imposed isolation tends to stimulate regression and rebellion in many people, the current situation no exception. For me, it stimulates regression as well as more rational, adult responses, and I can readily pinpoint the history and nature of the regression ‘button’.

Imposed isolation tends to stimulate regression and rebellion in many people, the current situation no exception. For me, it stimulates regression as well as more rational, adult responses, and I can readily pinpoint the history and nature of the regression ‘button’.

When I was just four years old (not that story again I can hear my kids groaning)

I was isolated in a hospital for infectious diseases for four weeks, very ill with diphtheria, followed by the vivid rash of scarlet fever. That hospital, the dark room, the kindness of masked nurses, and moving in and out of delirium, are my first memories – memories of imposed isolation. I was too ill to miss my family, but remember feeling a strange kind of comfort when I was told my father was in the same hospital.

When we were both well enough to be discharged, I remember walking in our local area with my parents and two year old sister, and neighbours crossing the street to avoid us. We weren’t contagious, but my unsightly, peeling skin convinced people they should keep a safe distance – all very confusing for a young, outgoing child.

My parents then chose isolation. We moved to the safe sanctuary of a family farm where we stayed until we were fully recovered. I imagine that’s where I first developed my love of nature, and of the animals who didn’t judge, or move away. I had a couple of caring relatives as well as my parents to help me fill each day with special experiences – the smell of home cooking, the pleasure of holding baby animals, listening to stories, making scrap books, drawing, growing plants, collecting insects, being in the fresh air, and using my imagination. When we returned home a month or so later we were ready to be re-engaged in life. But from that time, I always knew instinctively not to stand too close to people.

Both forms of isolation were necessary and helpful. The first, for my own safety and medical care, and for the safety of others in the community. The second, for my father and I to regain strength, and to learn how to take control of our lives again.

I imagine that life during and after COVID-19 might have some similarities to my early life experience, and many differences. I was a child after all, with little understanding of what was happening, much like small children at the moment, and of why people avoided me. The message I picked up was that for some reason it was unsafe for others to be too close to me, or that they felt unsafe if they got too close to me. Keeping a distance was to keep others safe, and me safe from feeling rejected.

Fortunately, my isolation was in a place that allowed me the freedom to run in the fresh air, discover new things, and enjoy the privilege of having adults read to me, play with me and assure me I was loved, despite my illness. I eventually learned how to entertain myself, how to structure my time, how to enjoy my own company and to find pleasure in being still and watching nature going on about its business. I had very little responsibility other than the simple chores I was given that made me feel useful.

The survival skills I learned at that time have stood me in good stead throughout my life, particularly when I have been acutely bereft, but I’m now wondering how well they might serve me in the midst of a pandemic. My time of isolation was limited – just over two months in all – when the social isolation we all face now has no foreseeable ending. And of course, many people have responsibilities which are likely to complicate this unchartered territory.

The Responsibility of Children

I don’t have the responsibility of young children these days, but can readily imagine how difficult it might be for parents trying to work from home, or those currently stuck at home without paid employment, as they struggle to navigate unchartered territory.

Information that many of us are receiving at the moment acknowledges the difficulty of keeping children entertained and co-operative 24/7. Home schooling, videos that encourage physical exercise, teach children how to play musical instruments or dance, and others that cover a range of simple, creative arts can help, but often for only short periods. What then?

Information that many of us are receiving at the moment acknowledges the difficulty of keeping children entertained and co-operative 24/7. Home schooling, videos that encourage physical exercise, teach children how to play musical instruments or dance, and others that cover a range of simple, creative arts can help, but often for only short periods. What then?

How do parents who are also experiencing ‘cabin fever’ mediate sibling squabbles, supervise school work, help children understand the new rules and remain co-operative? How do they remain tolerant of each other, and continue to express affection? I don’t know the answer.

What I do know is that stress tends to make all of us hit the ‘regression button’, and become an exaggerated version of our former selves. If we have taken stress out on each other in the past, we are likely to do so now; if we have always had difficulty being together 24/7, we are likely to find doing so extra difficult with an indefinite period of social distancing stretching in front of us.

My heart goes out to families living with domestic violence, alcoholism, drug dependence, personality disorders, depression, ADHD, oppositional behaviour disorder, and the extreme behaviour of some children on the autism spectrum.

It’s a rare family these days who doesn’t have first hand experience with observing, or trying to manage, at least one of these difficulties, meaning that I, and many others, can imagine what life might be like at the moment in families we care about.

But, as much as I care, as much as you may also be caring, I can’t think of anything that I would consider remotely helpful at this time, and I’m imagining you, the reader may be feeling the same. I’m sitting here with my fingers crossed, holding my breath, wishing I had a magic wand and hoping that some services in the community who have more specialised knowledge about how to manage these extremely stressful situations than I do might be providing help in some way.

And then there are the families living with chronic or life threatening illness, disabilities, loneliness, and grief. The threat of COVID-19 for some could be the straw that breaks the proverbial camel’s back. Feeling thoroughly helpless by now? Helplessness is likely to become a very familiar feeling for many of us in these troubled times.

Controlling what’s Controllable

What can we do to retain some feeling of control in difficult circumstances? I’ll list a few of my thoughts, and invite you to share yours. Mine are:

- Take one day at a time – treat each day as if this is all we have – don’t think too far ahead

- Maintain rules of SAFETY and RESPECT – physically and emotionally

- Have a family meeting to decide how these rules will be kept, and how ‘rule keeping’ will be rewarded or punished at the end of each day

- Discuss having a 0-10 stress rating and how each family member could signal when they’ve reached 7-8 on the scale and need time out

- Create a ‘time out’ spot where anyone can isolate themselves when they need a break – maybe a spot that includes head phones

- Plan a thanksgiving meal each week, where everyone is invited to express what they are grateful for

Adults living with Grief in times of Isolation

Grief is an isolating experience at the best of times. When we’re raw with grief we feel different to those who seem to be going about their normal lives without a care in the world. Not as different as we might imagine of course, because we haven’t really got a clue what anyone else is living with. New grief is so all consuming that it tends to shrink our world into a subjective circle of pain, temporarily clouding any previous objectivity that enhanced our ability to be empathic.

Some of us choose isolation for a time to ‘lick our wounds’; others feel isolated because people avoid them for fear of saying the wrong thing, or from an unconscious, superstitious fear of contagion. Whether isolation is a choice or not, grief is a lonely experience.

The Pollyanna version of our current enforced isolation is that, grieving or not, we are connected by many similarities; most of us are missing people we love, having difficulty structuring each day so that it has meaning and purpose, fearing further catastrophe, wondering what the future will be like, or if there will even be a future. We can all choose who we connect with, when and how; we can avoid people who make us uncomfortable, and we can decide how, when and where to express our grief. Some folk may find it easier to be expressive in writing than they can be face to face, and might choose to pour out their grief to family and friends in email or texts, or write to the NCCG outreach service.

My husband and I moved into a new home a heartbeat before isolation became the norm. The onerous task of unpacking has been made more manageable because we’ve been free from time pressure and distraction, and we’re grateful.

One of the first home-making things we did was to create a special corner in our very small garden where we can sit and remember the people we love who have died – a sacred, peaceful place. This space contains symbols that stimulate memories of specific people. Close by we’ve included symbols of the living people we love – a spot where we can sit, enjoy a cup of coffee, and talk about each one and their contribution to our lives. Coffee finished, we often head to our computers so we can write to the people we’ve been talking about to tell them what we’ve said, knowing how important it is to make sure they all know they are loved and appreciated. With fewer distractions, it somehow feels less difficult to reduce ‘unfinished business’, less tempting to put off till tomorrow the things we should say and do today.

Many of you may already have special ‘remembering places’ in your home, but if you don’t, I’d encourage you to think about what might work for you. Do you need a special spot to be alone with your memories, or would it work better if you had a space you could use as a family – perhaps talking about the person/s who has died in more detail, more depth than you might have for some time? Each person could take turns sharing a special memory, a quality of that person, and things that they miss. Would you do this at a particular time of day? How might you ‘set the scene’?

I don’t know about you, but I find ‘scene setting’ easier in autumn and winter.

I light candles, or sometimes a special lamp that belonged to loved relatives. Or – in the absence of a fireplace, we occasionally use a fireplace DVD to create the right atmosphere, knowing that something about watching a flickering light tends to stimulates memories and make it easier to talk, or just ‘be’.

Caring for Grieving Children in Isolation

Many of you already know that ‘A Friends’ Place’ will continue to provide support services throughout this time of global crisis. The way in which the service is delivered has of course changed from face to face counselling and support, to zoom, Face Time, phone call, email and SMS.

Many of you already know that ‘A Friends’ Place’ will continue to provide support services throughout this time of global crisis. The way in which the service is delivered has of course changed from face to face counselling and support, to zoom, Face Time, phone call, email and SMS.

Many of the things I’ve already mentioned are relevant for helping children in your care, but I’ll repeat and summarise them so you don’t have to plough through a zillion words to get to them, and I’ll also include some additional ideas.

One of the things I want to encourage you to try is getting your children to keep a diary of their experience of living with grief in isolation. You could enthuse them by truthfully saying ‘one day, you may be able to write a book, or an article, and have it published.’ I imagine records of personal experiences will be in high demand in the fullness of time, but even if they aren’t, their personal record may prove invaluable for re-reading in the future, and eventually for reading to their own children and grandchildren.

But, back to the present – I imagine grandparents and other relatives in the here and now might value receiving excerpts from these very personal journal entries as a way of staying in touch.

Older children could record their experiences in a traditional journal, or create a Word document on their computer. Thoughts, feelings, illustrations, suggestions could all be helpful for the writer and for those who are privy to reading them. Encourage older children to describe what helps each day, and what makes things worse. Where and how does the person who died fit into this strange, new experience? Do they talk to them? Wish they were here? Feel glad that they are spared the frustration and anxiety? Are they angry that person isn’t here to help them/be with them now? What would be different if they were here? How is this experience affecting their own dreams and hopes for the future? Their thoughts about a career? Could they make a graph of their moods and what they believe influences fluctuations? What skills have they developed in being able to change a particular mood?

Older children could record their experiences in a traditional journal, or create a Word document on their computer. Thoughts, feelings, illustrations, suggestions could all be helpful for the writer and for those who are privy to reading them. Encourage older children to describe what helps each day, and what makes things worse. Where and how does the person who died fit into this strange, new experience? Do they talk to them? Wish they were here? Feel glad that they are spared the frustration and anxiety? Are they angry that person isn’t here to help them/be with them now? What would be different if they were here? How is this experience affecting their own dreams and hopes for the future? Their thoughts about a career? Could they make a graph of their moods and what they believe influences fluctuations? What skills have they developed in being able to change a particular mood?

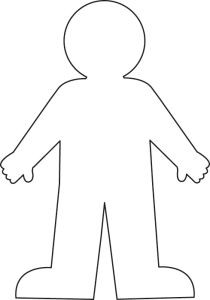

Young children could do a version of what I’ve suggested for journal entries for older children, but do so in a scrap book. Instead of writing, they could use the image of a person (illustrated below) to show what they feel each day, where they feel it, and how strongly.

Parent’s Role – explain the exercise, and why they’re doing it. Sit quietly until they finish, then facilitate the experience by asking the questions I’m suggesting. You might do a version of the exercise yourself so that they don’t feel as if they’re being observed or analysed. At the end of the exercise, let them know that they can also ask you about your picture if they want to.

Say: We’re going to imagine this is our body, and use coloured pens/pencils to show the place in our body where we have a feeling right now. We’ll each decide what colour each feeling is (sad, happy, angry, scared, jealous, bored) , and how big the feeling is. How about we start with ‘angry’ and so on…Any order is ok.

When you’ve both finished the exercise, and shared your drawings and explanations, you could then ask your child ‘what do you need to make you feel less …(angry, sad, bored, jealous) and what do you need to make you feel more…(happy)?

If you chose, you could do the same about you. There is no right or wrong answer in this exercise, but the rules of SAFETY and RESPECT are important. Don’t criticise, lecture or try to ‘fix’ everything – focus on what is practical and relatively easy to change. Resist the temptation to analyse the meaning of the colour children use. For example, black for some children represents softness, safety, a place to hide when they need time out, and so on. Don’t assume the use of black means that your child is depressed – ask what each colour means to them.

Summary – Caregiving for Grieving Children in times of Isolation

- Have a family meeting to establish rules – SAFETY and RESPECT – body, mind, possessions. Daily rewards for keeping rules? Punishment for breaking rules?

- Monitor stress levels – 0-10. When anyone’s stress level reaches 7/8, they can ask for time out or be encouraged to take time out

- Make a ‘time out’ spot in the home – should be comfortable and relaxing, if possible.

- Create a remembering place, for individual and for family use

- Have a ‘thanksgiving dinner’ at least once a week. Acknowledge the good things each person has done or experienced

- Children and young people create a journal to record their experience of grief in a time of enforced isolation

- Share appropriate journal entries with important relatives and friends

- Create board games, crossword puzzles and word games involving grief and isolation – include fun aspects when possible

- Write stories that other bereaved children and young people might appreciate and send them to the NCCG (‘A Friends’ Place’) to see if they are suitable for publication in the newsletter.

- Create a treasure hunt for the whole family – include clues that include the person or persons who died

- When you need extra help, call or email ‘A Friends’ Place’.

Help

Help is always available – at ‘A Friend’s Place’ or by contacting our outreach service.

Dianne McKissock OAM

NCCG Outreach Support Service

Email support for dying and bereaved people and anyone involved in their care