A Time to Live and A Time to Die

In a perfect world there is meant to be a natural order to life, a predictable sequence of events that makes us feel secure. Like old people dying before the young. When the order is reversed, we regress, feel insecure, and struggle to find logical or illogical ways to convince ourselves that we won’t also be the victims of unpredictable happenings. Earth quakes, tornados, famine, and tsunamis happen in other countries, surely not ours? Harder for us to put our head in the sand about fires, devastating accidents, floods and drought.

We may cling to the hope that death is meant to come quietly and naturally to very old people as they sleep, not to babies, children, young adults or people in the prime of life. But, no matter how closely a death conforms to our hopes of a ‘natural order’, I know that the death of a partner, an older family member or friend can also be devastating, depending on the manner of death and the relationship we have with that person. If we too are old, we may have little to look forward to and may find it difficult to build enough life around the emptiness of grief to sustain us. In these circumstances we are dependent on the compassion of others, our memories, and our philosophy of life to help us find reasons for going on.

Hopefully, as we age, or even before that, we will talk about death with those close to us, and plan, at least intellectually, how we might manage without their physical presence. No matter how and when the death of a loved person occurs, we react differently when we can make sense of things, when we can predict outcomes and rehearse for the future. Premature and sudden death deprives us of these opportunities.

Bob Hawke’s recent death at age 89 highlighted some possible differences in our reactions when a death is seen as ‘timely’ to the way we tend to respond to what is socially deemed ‘an untimely death’. Bob was ready to die and said so, openly. His stated reason for being, to contribute to the society he loved and served, had come to an end. His wife and surviving children undoubtedly feel sad and will miss him daily; his colleagues and friends will miss him, and his country will remember him with affection.

Bob Hawke’s recent death at age 89 highlighted some possible differences in our reactions when a death is seen as ‘timely’ to the way we tend to respond to what is socially deemed ‘an untimely death’. Bob was ready to die and said so, openly. His stated reason for being, to contribute to the society he loved and served, had come to an end. His wife and surviving children undoubtedly feel sad and will miss him daily; his colleagues and friends will miss him, and his country will remember him with affection.

Bob was a gregarious, charismatic man of the people, a larrikin in the familiar Australian way: unpretentious, expressive, not ashamed to show tears when he was touched, given to heavy drinking on occasions, and to using colourful language. He was intelligent and academically successful in Australia and in England and began his public career here as a Trade Union Leader. Labour’s most successful leader, he won 4 consecutive elections and managed to skilfully walk the tightrope between the left and the right, business and unions, Labour and Liberal.

Older folk like me will remember his support of indigenous Australians, his unsuccessful (so far) fight for them to have a treaty similar to that of indigenous New Zealanders; the way he strengthened Australia’s alliances with Asia, floated the Australian dollar, and introduced our internationally admired Medicare Health Care System. Memories will be passed down through his family members, his political colleagues, and to coming generations via biographies and history books.

Bob’s death is certainly sad for those closest to him, but I don’t imagine it is devastating. He achieved most of his life’s ambitions and died in the fullness of time. Eighty-nine years is considered ‘a good innings’ by anyone’s count, and he died of natural causes, leaving little unfinished business. That we know of anyway.

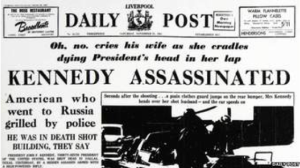

Compare Bob’s death to the worldwide reaction to the death of President John Kennedy. Young, good looking, charismatic, with a beautiful wife and two small children, he was assassinated in his prime. We all watched the graphic images on TV, horrified and disbelieving. We grieved vicariously as we felt compassion for his wife, his children, his extended family and his country. We struggled to make sense of what had happened and refused to accept simple explanations. Conspiracy theories flourished and still do in many people’s minds. Innocence was lost, trust shattered.

Compare Bob’s death to the worldwide reaction to the death of President John Kennedy. Young, good looking, charismatic, with a beautiful wife and two small children, he was assassinated in his prime. We all watched the graphic images on TV, horrified and disbelieving. We grieved vicariously as we felt compassion for his wife, his children, his extended family and his country. We struggled to make sense of what had happened and refused to accept simple explanations. Conspiracy theories flourished and still do in many people’s minds. Innocence was lost, trust shattered.

This was not the natural order of things. He should have lived to see his children grow up, fulfil his ambitions, and contribute to life in many meaningful ways. He should have tidied up any unfinished personal or political business, then died peacefully in his sleep of old age. We know that his family was devastated – we have seen the effects played out over the years from the time we tearfully watched John junior saluting his father’s coffin as the funeral cortege passed, to the bravery required by Caroline to soldier on despite her father’s, her uncle’s, her mother’s and then her brother’s untimely deaths. Wealth gave her no protection other than the ability to hide away from public scrutiny when she needed to lick her wounds.

This was not the natural order of things. He should have lived to see his children grow up, fulfil his ambitions, and contribute to life in many meaningful ways. He should have tidied up any unfinished personal or political business, then died peacefully in his sleep of old age. We know that his family was devastated – we have seen the effects played out over the years from the time we tearfully watched John junior saluting his father’s coffin as the funeral cortege passed, to the bravery required by Caroline to soldier on despite her father’s, her uncle’s, her mother’s and then her brother’s untimely deaths. Wealth gave her no protection other than the ability to hide away from public scrutiny when she needed to lick her wounds.

When Diana, Princess of Wales, died tragically in Paris, she left her two young sons devastated by grief and a world reeling from shock. Young and beautiful, a constant everyday presence in our lives via the media, Diana carried the projected, fairy tale dreams of young women everywhere, and many men it seems. She brought royalty closer to the people, was vulnerable like the rest of us, openly demonstrated her love for her children and made meaningful contributions to life. Diana used her position to draw attention to the needs of people with HIV, the needs of the elderly, the poor, the ill and the disenfranchised, and to the horror of land mines. Her untimely death, while she was still young and beautiful, stimulated a tsunami of grief, probably a mixture of genuine sadness for her loss, sympathy for her sons, and the projection of unexpressed sadness carried by ordinary people everywhere.

When Diana, Princess of Wales, died tragically in Paris, she left her two young sons devastated by grief and a world reeling from shock. Young and beautiful, a constant everyday presence in our lives via the media, Diana carried the projected, fairy tale dreams of young women everywhere, and many men it seems. She brought royalty closer to the people, was vulnerable like the rest of us, openly demonstrated her love for her children and made meaningful contributions to life. Diana used her position to draw attention to the needs of people with HIV, the needs of the elderly, the poor, the ill and the disenfranchised, and to the horror of land mines. Her untimely death, while she was still young and beautiful, stimulated a tsunami of grief, probably a mixture of genuine sadness for her loss, sympathy for her sons, and the projection of unexpressed sadness carried by ordinary people everywhere.

People struggled to make sense of Diana’s death, as we always do when death is sudden and unexpected and were unable to find a factual explanation big enough to fit the hugeness of the shock. Conspiracy theories flourished once again.

We could all write a list of people who died ‘before their time’ – Michael Hutchence, Heath Ledger, Steve Irwin and Philip Hughes quickly come to mind, and there are many, many others. Most of us have examples in our own families. I know I do.

What Impact do the sudden or Untimely deaths of famous people have on those already Grieving?

Timely or untimely, sudden or perhaps expected, the death of someone famous tends to have an impact on anyone already grieving and vulnerable. The effect can be positive or negative, but more often than not, the effect is both.

Communal or public grief has the potential to legitimise the intensity of our own feelings and behaviour – to make both seem as normal as we know them to be. On the other hand, we may resent the attention given to this person, this family, when we believe our grief is just as worthy of compassionate understanding and support. It’s easy to feel resentful, to want to scream at the universe – ‘Doesn’t anybody care that my…is dead?’, ‘Doesn’t anybody know that I need support?’, ‘Doesn’t anybody know that I think the person I love is as worthy of praise as the famous person you’re all making such a fuss about?’, ‘Why is that person’s death more important?’

Once rightful indignation has subsided, we might choose to use the residual energy to adapt ideas from public grief rituals to create a fitting memorial for the person we love and grieve.

Timely or not, sudden or anticipated, death is a reminder to us all to live as many moments as possible as if they were our last. But, we can’t live in a perpetual ‘state of grace’. We may clear the slate of unfinished business today, but life keeps happening. What we can do is tell important people that we love them, give praise where it’s due, appreciate what we have, and enjoy the beauty of the environment. We can tell people when they hurt or annoy us and do so in a way that makes it possible for them to apologise. We can use our anger energy to fight for important causes, to defend people who are vulnerable, to right as many wrongs as possible. We can relax, have fun, laugh, play; we can feel fully alive now, today, because all too soon it will be our turn to die.

I think the fairness/unfairness aspect of untimely death and sudden death was summed up beautifully by a little boy I was working with some years ago. He looked at me as we played and said ‘Di, you’re old, I think you’re going to die before me. Will you tell God how angry I am with him for taking my baby brother?’

Folk of my vintage might remember Pete Seger’s song ‘Turn, turn’, adapted from the biblical book of Ecclesiastes. It has a catchy tune that is easy to sing or whistle as you work, and that’s something that I, like my sisters, have always done. I guess it would have been surprising if we hadn’t developed that unconscious habit when it was something both our parents modelled, in the house and in the garden.

I find myself whistling or quietly singing ‘Turn, turn,’ when my spirits are flagging, a reminder to embrace my own grief, be compassionate about other people’s, famous or not, and get on with the complex job of living.

Help

Help is always available – at ‘A Friend’s Place’ or by contacting our outreach service.

Dianne McKissock OAM

NCCG Outreach Support Service

Email support for dying and bereaved people and anyone involved in their care