Funeral Rites & Funeral Rights

My dearly loved father died in the middle of the night.

Five hundred miles away, I was sleeping soundly after a food deprived day at a health farm, a treat paid for by the friend sharing my room. We were woken by a loud knock on the door, that sound marking the beginning of the long trek to join my family. On the way to the airport the old car my friend was driving kept running out of water and we had to stop every few kilometres to refill, a process made more difficult because we kept doubling over with laughter as we imagined how we must look , still in our pyjamas, to passing motorists. We were glad it was still dark.

Reality took a while to catch up. I managed to get a sympathy seat on the first plane heading north, by now changed out of my pyjamas, and spent the hour or so in mid air thinking of my father and feeling close to him – as if he was beside me. Regressed already, I convinced myself that being in the air as the day dawned, above the rush and bustle of everyday activities, facilitated a calming, spiritual connection.

My mother, sisters and I spent the following day organising the funeral. In the evening we were visited by a couple who had been neighbours of my parents for more than 30 years. They were dressed in their best clothes, and sat formally and stiffly in the high backed chairs in the lounge room. ‘We don’t like funerals’ they announced as they explained their visit to pay their respects. ‘We won’t be at the service.’ When they left, one of us voiced the question ‘are we meant to like funerals?’

Somehow, we thought that liking them might be an indication of psychopathology, but we all believed they were important. We also had an idea of what might be described as a ‘good’ funeral’ or a ‘bad funeral’, different for each one of us.

One Version of a Good Funeral

My father’s funeral, four days after his death, was dignified and respectful, the church filled to overflowing. It certainly met my mother’s needs, which was important to us all. In the preceding days my sisters and I, our husbands and children, visited the funeral home to spend important time with our father and grandfather. Our mother found the thought of seeing him dead too confronting and we understood her needs. We supported her decision after making sure she would have no regrets.

Those visits to spend time with dad were important. We talked to him, told stories about him, laughed and cried, held his hands, and left our lipstick coloured kisses all over his face. We thought he looked handsome and peaceful, his face unlined by wrinkles. Mum allowed us to tell her every detail, her imagined version soft and non threatening. One of my nieces was away from home at the time and missed those special shared moments, her regrets still strong years later.

Good Funerals & Bad Funerals

My thoughts about funerals, and judgements about ‘good’ or ‘bad’, are personal and in no way meant to be a criticism of the timing and conduct of funerals that follow traditional religious and cultural practices. For anyone interested in learning about funeral services around the world, I recommend the book’ The Last Dance’ by de Spelder and Strickland.

Those of us raised in a liberal, more secular environment tend to have very individual needs around all aspects of dying, death and bereavement. But, having already acknowledged the importance and impact of religious and cultural practices, I have counselled folk, mostly women, whose needs weren’t met within traditional guidelines, particularly after the death of a child. In the freedom and safety of the counselling room they were able to imagine a funeral that was closer to their ideal, and in so doing, release emotions that had felt constrained. Their tears, or ‘liquid love’ as my husband calls them, were calming, and helped them to feel closer to the person who had died.

So, what makes a funeral ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for many of us? That might seem like a strange question when we all know that funerals may feel ‘bad’ because they acknowledge the death of someone we love or who is important to us in some way. But the obvious aside, what elements are important to most of us?

Funeral rites are as old as the human race. Every culture, every civilisation, has taken care of their dead and had some kind of rite, ceremony or ritual. Most have had sacred places for the dead where they created memorials, initially very simple and natural, like stones piled on top of the grave.

The manner in which bodies were cared for after death was usually determined by geography. For example, in countries where the ground was too hard to dig a grave, bodies were placed in trees or on a platform in the open, or sometimes just lying on rocks.

In modern Australia, it isn’t geography that determines what we do with the bodies of those we love after their death. Funeral rites and ‘disposition’ are more likely to be the result of cultural or religious customs and expectations, and sometimes from missing or misguided information.

Unfortunately, funerals these days sometimes tend to be experienced as an endurance test, rather than an important opportunity to celebrate the life of someone we love, and to receive loving support from a caring community of relatives, friends, colleagues and neighbours. Many of us feel pressured into holding a funeral service as quickly as possible after the death occurs, perhaps in the mistaken belief that we have no choice about a time frame, or that getting the funeral over and done with means that we can put ‘it’ all behind us and get on with life. If only it worked that way!

When a funeral takes place 3-4 days after the death of someone we love, many of us will still feel numb with shock and be unable to think clearly. Others will be numb as the result of tranquillisers, alcohol or other drugs, but whatever the cause of our inability to be fully present, we may later come to resent the fact that we can’t remember important details of the service. Making sure the funeral service is recorded can be important not only for family members who can’t remember details, but for those unable to attend.

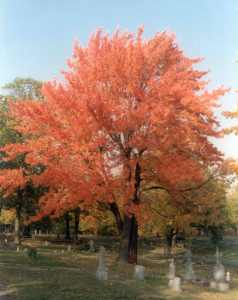

I know I would have preferred to wait longer than four days for my father’s funeral. His death still didn’t seem real to me, a sense of unreality that was compounded by the party like atmosphere of the ‘wake’ that followed the service. I chose to leave the gathering of family and friends and sit with my husband at my father’s newly dug grave. The feel of the soil, the silence of the cemetery, and being surrounded by the graves of other loved people who had died, soothed my soul. There, I could think my own thoughts and not have to perform or live up to the expectations of others. My husband was comfortable sitting quietly with me, holding my hand, just understanding.

My mother’s funeral wasn’t held until about 8 days after she died. I was working in New Zealand at the time and my family was very willing to wait until I could complete my commitments before joining them. Once again, we spent time with my mother’s body, all benefiting from that special, intimate experience. We also had two services – one in the town she was living in at the time, the other where she had spent most of her life. The fact that everything was slowed down allowed us all time to acknowledge the reality of her death, and to think as well as feel, to appreciate, celebrate and give thanks for her life.

My mother’s funeral wasn’t held until about 8 days after she died. I was working in New Zealand at the time and my family was very willing to wait until I could complete my commitments before joining them. Once again, we spent time with my mother’s body, all benefiting from that special, intimate experience. We also had two services – one in the town she was living in at the time, the other where she had spent most of her life. The fact that everything was slowed down allowed us all time to acknowledge the reality of her death, and to think as well as feel, to appreciate, celebrate and give thanks for her life.

Extrapolating from what I have just said, I think one of the most important aspects of a ‘good funeral’, for people like me, is the opportunity to slow down. Slowing down gives us time to feel, to think, to tell stories, to plan a funeral that truly acknowledges the personality of the person who has died, and that honours their contribution to life. A well planned funeral can feel like a gift to the person we grieve – a way of saying ‘I knew you well, this is what I experienced of you, this is how you have touched my life and this is my assurance that you will never be forgotten.’

However, I freely acknowledge that for many folk, following familiar religious and cultural beliefs and practises may give them the same sense of comfort and security that people like me derive from having more say about the timing and content of a funeral service.

Pressure to hold a Funeral within three days

Many people believe that they have no choice about postponing a funeral. Religious practices aside, this idea has often been the result of pressure from family members who may believe it is in our best interests to get ‘it’ over quickly, and from funeral directors who often time funerals for their own convenience rather than to meet the needs of grieving families.

Many people believe that they have no choice about postponing a funeral. Religious practices aside, this idea has often been the result of pressure from family members who may believe it is in our best interests to get ‘it’ over quickly, and from funeral directors who often time funerals for their own convenience rather than to meet the needs of grieving families.

Burying people three days after death made sense in times past when it wasn’t possible to control body temperature with refrigeration. In many cultures, when burial after 3 days was necessary for health reasons (religious interpretations came later), families kept vigil with the person they loved, and gradually adapted to their new reality as bodily changes occurred. Other members of the animal world of which we are part, have similar practices around staying with the body for three days – elephants and kangaroos are good examples.

These days, many people don’t get to spend significant, intimate time after death with the person they love, and later have regrets. If the body has been disfigured in any way, they may be actively discouraged by family or funeral directors with the words ‘it’s better to remember them the way they were’. Those words imply that remembering the person the way they were would be impossible if we were confronted with graphic images.

For some people that may be true, and their choice not to see or spend time with a loved person after death should be respected. However, in our long years of experience working with bereaved people, we have found that, despite severe disfigurement in some cases, many family members have benefited from ‘being with’, or being near, the body of someone they love.

When the death has been sudden, traumatic, suspicious, or in the immediate aftermath of surgery, initial ‘viewings’ (using the language of the funeral industry) often take place at the morgue. While the setting might not be ideal, we know a number of sensitive and skilled forensic social workers who prepare the family for what they might experience at a sensory level, and guide them gently through the process. Disfigured body parts can be discretely covered so that family members have a choice about what they see or touch. Sometimes just being able to stand near the body of someone we love might be enough to meet our needs for intimacy – it’s having choice that is empowering.

When a child dies suddenly or in distressing circumstances, some creative and caring social workers ask the family what would make them feel reassured that their child was cared for at the morgue. Volunteers make special teddy bears that may be placed in the child’s arms as a gesture of caretaking until parents can bring the child’s own toys to place with the body, an image that always brings warm tears to my eyes.

Sometimes people express anger or frustration when a funeral has to be delayed indefinitely because an autopsy is involved. I understand how difficult it might feel to have the body of someone we love lying for days in a cold, clinical environment, and think this is one of those times when thought blocking and distraction can be helpful. I know that’s one of the strategies I used when my daughter died.

That aside, I think most of the difficulty around the time frame lies in comparing the traditional 3-4 days between death and funeral with the longer time frame caused by the needs of the coronial system. If we drop the comparisons we can choose to see the delay in a positive light. Time delays give us an opportunity to think as well as feel, and to prepare the kind of meaningful funeral service that feels like a gift of love and appreciation to the person who has died.

Community groups in a number of areas in NSW, and I imagine also in other states, make it possible for family members to be actively involved in preparing the body of their relative for burial, bathing them, dressing them in clothes of their choice, and making sure their hair is the way they or the deceased person liked it. The process can be so gentle and loving that it feels like tucking someone we love up in bed for the last time, leaving a very special, poignant memory.

Children and adults may be able to decorate the exterior of the coffin, and place gifts, letters and photos inside. Simple, personal, intimate and slow seem to be ingredients in the process that many of us find therapeutic. An expensive coffin and a sophisticated, carefully, and thoughtfully choreographed funeral are right for some families, but not for others. The more the funeral represents the way each family lives their life and relates to the person who has died, the more satisfying it is likely to be in the long term.

Family Conversations about Life, Living, Dying & Death

Ideally, all of us would talk about dying, death, funerals, burials, cremations and so on as a natural part of our conversations about life and living. Unfortunately, we tend to prevent such important conversations by hanging onto a superstitious belief that ‘talking about such morbid things will make them happen’, or by naively believing that death is what happens to other people, other families.

Ideally, all of us would talk about dying, death, funerals, burials, cremations and so on as a natural part of our conversations about life and living. Unfortunately, we tend to prevent such important conversations by hanging onto a superstitious belief that ‘talking about such morbid things will make them happen’, or by naively believing that death is what happens to other people, other families.

Knowledge can be power in times of family vulnerability, and naivety disempowering. If we know what we want, what our family wants, what rights we have, and who we can trust to call on as an advocate while we have difficulty thinking clearly, we are more likely to have special, intimate time with the person who has died, and the kind of funeral that leaves poignantly beautiful memories. We may not have had control over the death of the person we grieve, but we can have as much control as possible over the way we celebrate their life.

Funerals are for the living and done well, have the capacity to enhance life. They can leave us, the mourners, feeling proud of the way we acknowledged and celebrated the life of the person we loved, and expressed our grief in whatever way felt right for us. Or we can be left with regrets.

The Next Best Thing

If you have been left with regrets about the way the funeral of the person you love was conducted, talking to an empathic friend or relative can help. Some folk find benefit from talking to a skilled bereavement counsellor who will help them design, in imagination, the perfect funeral they longed for. When that happens, our body reacts ‘as if’ the imagined service actually happened, changing our body chemistry in a way that is therapeutic.

Help

Help is always available – at ‘A Friend’s Place’ or by contacting our outreach service.

Dianne McKissock OAM

NCCG Outreach Support Service

Email support for dying and bereaved people and anyone involved in their care